Ellis Stacey is working on a PhD on British book culture and the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s. You can follow him on Twitter @corduroycheeks

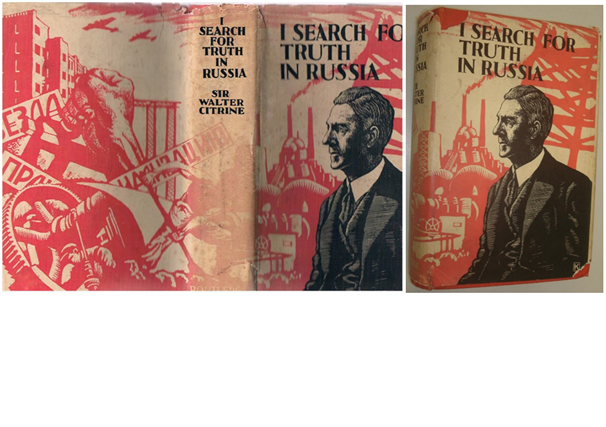

Two copies of Sir Walter Citrine’s 1936 book I Search for Truth in Russia (London: Routledge, 1936) feature in the images above. Taken from product listings on the popular online literary marketplace abebooks.co.uk, they are ‘seller-supplied images’ produced with the express intention of attracting the flitting gaze of the potential buyer as he or she scrolls and scans up or down the backlit page.

With the internal written content obscured, the photographs present us solely with the outward appearance of each volume. Left with nothing but an object to appraise, our attention is forcibly turned from considerations of the text to the rare and valuable dust-jacket with which both books are adorned; to the striking contrasts of colour and the sharp crisp detailing of the woodcut printed portrait of the author and his disorderly industrial surroundings.

Despite the centrality of books to the practice of history and the wider arts, book-jackets – and particularly the behind-the-scenes processes and decisions that fashioned their creation – have been almost universally overlooked.

Using the jacket produced for Sir Walter’s book as something of a “hook,” this blog post aims to go some way towards rectifying this oversight; championing them – and other forms of publishing paraphernalia – as historical artefacts worthy of attention.

The book itself is a monographic version of a travel-diary kept by Sir Walter – at the time of publication the General Secretary of the Trades Union Congress – during a visit to the USSR he, and his wife Doris, had made in the autumn of 1935.

Having been invited by the Russian authorities, the keen-sighted conjugal pair toured the Western Soviet Union for just over a month; travelling from Leningrad in the North to the southern Grozny oilfields and “The Black City” of Baku on the shores of the Caspian Sea.

Figure 2: Map of Sir Walter and Doris’s route. Printed in I Search for Truth in Russia (London: Routledge, 1936), p. xii

Under the auspices of the official Soviet travel agency Intourist and their ever attentive guides, an exhausting itinerary saw them briskly perambulated from ball-bearing factory to underwear factory; from motor works to rest homes and on further still to Palaces of Industry, Collective Farms, towering urban housing projects and partially constructed hydro-electric plants in the Caucasus Mountains.

Although impressed by Soviet welfare provision and the vast scale and ambition of what he saw, the prominent Trade Unionist painted a bleak picture of life under Communism. He was appalled by the standard of housing, balked at the high-cost of basic consumer goods and was disappointed to observe ‘something dangerously like social distinctions’ creeping into public life. Towards the end of his trip he concluded that, despite being nominally in control of the reins of power, the Russian worker existed firmly under the heel of an undemocratic and repressive police-state which, in its methods at least, was almost indistinguishable from the Fascist regimes of Germany and Italy.

‘Keep at them with incessant propaganda!

Propaganda! Propaganda! – from morning to night.

On the wireless, films, pictures, posters, text-books, follow them everywhere.’

Sir Walter Citrine, I Search for Truth in Russia (London: Routledge, 1936), p. 254

Having read the book, I came across its jacket by a rather unusual and strangely indirect route. In fact, it may come as a surprise to hear that I have never really encountered it at all – the pictures presented above are the closest I have come to experiencing it first-hand.

I found it – or, to put it more accurately – I found the fragmentary archival traces of its conception, at the University of Reading’s Archive of British Publishing and Printing whilst looking through the correspondence files of the book’s publisher, the firm of Routledge & Kegan Paul.[1]

I was confronted with a conversation, conducted via letters and postcard notes, between three men: the author Sir Walter, the TUC’s experienced Publicity Officer Herbert Tracey – who acted as Citrine’s representative due to the General Secretary’s heavy workload – and Routledge’s Managing Editor T. Murray Ragg who was overseeing the publication.

Demonstrating the extent to which publishing was – and remains – a collaborative enterprise, it was these three men who, in a series of wrangling, fraught and at times tense discussions debated about and finally decided upon the jacket’s design.

As the literary theorist Gérard Genette tells us, the jacket (often called a dust-jacket or cover) is a key component of any book’s paratextual apparatus: those circumambient ‘verbal or other productions’ that, by surrounding and interacting with the central text, provide the means by which it ‘makes a book of itself and proposes itself as such to its readers, and more generally to the public.’ Conceptualised spatially as an intermediary field placed between text and reader – a ‘threshold’ or ‘vestibule’ – these paratextual elements are not benign supplements to the text but fundamentally affect its meaning.[2]

Focusing on jackets – and particularly any materials which provide an insight into how and why they were created – therefore allows us to examine how books were assembled and presented to readers and glimpse the variety of mediating factors involved, whether commercial, personal or political. The processes and politics of book-presentation are revealed.

Before we return to Citrine’s case, indulge me as I make a few preliminary statements about book-jackets in the 1930s.

Despite having existed, in one form or another, since the early-to-mid-nineteenth-century, the arrival of mass culture and the commercialisation of the publishing industry in the early-twentieth-century transformed the physical appearance of books and instigated something of a visual revolution within the book-trade. Driven by the desire to exploit an expanding market, jackets became increasingly salient and their designs became more elaborate, pictorial and colourful.

Figure 4: Examples of 1930s book-jacket design taken from Books about Russia. From http://www.abebooks.co.uk/mw-books-ltd-galway/3249244/sf

For many commentators, the new “poster-like” jacket signalled the book-trade’s entry into modernity. As Thomas Foster – providing one of my favourite quotes – eloquently wrote in 1933:

‘Books, as all else, reflect the spirit of a time which expresses itself in other directions through the brightness of neon signs, Fair Isle pullovers, platinum-blonde hair and red-enamelled finger-nails. To-day, a booksellers’ shop resembles nothing so much as a poster hoarding; yet it is not books which are thus displayed, but book jackets…’

With the public’s ‘modern tendency towards brightness and colour’ firmly entrenched, Foster continued, the jacket had become ‘an integral part of the modern book.’ Tellingly, works of non-fiction, such as those from the ‘sober realms of biography and history,’ had not remained unaffected and even ‘such aridities as scientific and technical publications’ were adopting the ‘fashion’ and wearing the á la mode ‘pictorial dust-cover.’[4]

The book-jacket, therefore, mattered. Creating an ‘attractive and effective design,’ Ragg explained to Tracey, would be ‘very important from the selling point of view.’ It would play a key role in representing and advertising the diary to the potential purchaser as he or she passed by the bookshop window and, significantly, to preliminary buyers in the wholesale and retail trade.

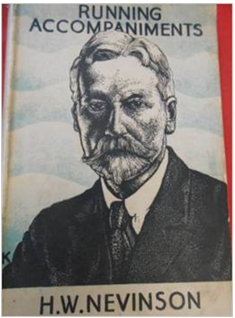

Ragg’s initial suggestion for the jacket allows us to map channels of artistic influence and demonstrates the ways in which successful designs were regurgitated and adapted for subsequent projects. Routledge had recently published a work of reminiscences by the world-renowned journalist H.W. Nevinson entitled Running Accompaniments. Impressed by the simple eye-catching form of its cover, Ragg suggested that the same artist – the Australian William Kermode – be commissioned to produce a similar arrangement for the Russian diary; as was the case with the parent design, a portrait of the author, reproduced by the artist from a photograph, would provide a focal point and stand out against a red background.

Figure 6: Figure 7: The Inspiration. The dust-jacket for H.W. Nevinson’s Running Accompaniments (London: Routledge, 1936). From http://bit.ly/1PxlDBX

The trio were in agreement regarding the centrality of Citrine’s portrait: a stylistic feature that drew upon the good-name, social standing and cultural authority of the author, but the make-up of the background proved highly contentious.

Ragg, keen to conform to the generic tropes of the “Books about Russia” genre and trade upon the relatively positive public image that the Soviet Union was enjoying in Britain at the time, advocated a vivid red ‘symbolic composite design’ made-up of the instantly recognisable insignia of the communist creed: ‘a hammer and sickle and other Russian emblems or typical scenes.’[5]

Citrine, as a moderate leftwinger and vocal anti-Communist, had strong feelings about the potential connotations that such a design might evoke and rejected it outright. With his portrait featuring so prominently, Citrine’s book-jacket would not only advertise the volume, it would also visually represent, and increase the public visibility of, its author. With this in mind, Sir Walter was intensely nervous about publicly displaying any material that might create a visual association between himself, communism, and its Soviet heartland at a time when he was actively engaged in opposing calls from the British Communist Party, and other members of the Left, for a progressive anti-Fascist “United Front” and military alliance with Russia.

Citrine’s book, as the letters detail, was intended to counter perceived untruths, about the apparent wonders and didactic achievements of Soviet society, being circulated by those of the Fellow-Travelling intellectual Left, the CPGB and the cultural institutions of the Popular Front.

The jacket availed Citrine of the opportunity to distance his work from similar – and predominantly pro-Soviet in their tone – books on the market: an act of authorial and literary positioning.

The General Secretary’s concern was so acute that he even challenged, after being presented with each of the latest proofs, the shade of red being used. He continually requested, to Ragg’s annoyance, that the ‘heavy and lurid’ background tones be lightened; literally avoiding any association with the “Reds.” [6]

Eventually Ragg convinced the author to relent, reassuring him that the colour – being already ‘about fifty percent white, fifty percent red’ – was ‘very far from the glaring, pillar-box red generally used for books about Russia.’[7]

Here, abruptly, the trail runs cold. The final details of the discussion are lost to us: carried out in-person, over the telephone, or simply missing from the archival files.

Here also, I must stop.

I’m afraid my conclusions are far from sophisticated and succinct; I’ve used – perhaps abused – the informal and non-prescriptive blog format to present ideas and material still raw, half-formulated and highly suggestible.

Thinking critically about book-jackets and related classes of literary ephemera forces us to (re)visualise the books we study; to recognise the importance of the visual in the communication of ideas through the medium of books. By extension, we are further cajoled into appreciating books – in Modern Britain at least – as commodities operating within, and profoundly influenced by, consumer society. Non-fiction in particular has often been perceived as existing above of, or aloof from, the demands of the marketplace, yet Citrine’s case – and similar research that I, and others, have carried out – problematizes such assumptions.

Going deeper – past the palimpsestic final product and into the archives of publishers and authors – allows us to humanise the publishing process; so often assumed to be mechanical, mundane and platitudinous. We see that authoring and presenting a book to market – especially highly personal or potentially politically inflammatory works of life-writing – could be an anxious, taut and contentious process as multiple exigencies interacted, combined and conflicted.

The next time you find yourself confronted with a tattered copy of a century-or-so old book, clad in nothing but a fading cloth binding, think: did it always look this way?

Further Reading:

For more on book-jackets see, for example.

- Baines, Penguin by Design: A Cover Story 1935-2005(London: Allen Lane, 2005)

- Connelly, Faber and Faber: Eighty Years of Book Cover Design (London: Faber, 2009)

- Drew and P. Sternberger, By Its Cover: Modern American Book Cover Design (New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 2005)

- Powers, Front Cover: Great Book Jacket and Cover Design (London: Mitchell Beazley, 2001)

- Thomas Tanselle, ‘Book-Jackets, Blurbs, and Bibliographers’, The Library, 26:2 (1971), pp. 91- 134

- Thomas Tanselle, ‘Dust-Jackets, Dealers, and Documentation’, Studies in Bibliography, 56 (2003/2004), pp. 45-140

- Thomas Tanselle, Book-Jackets: Their History, Forms, and Use (Charlottesville, Vir.: The Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, 2011)

[1] RKP 28/7: Letters to and from Walter Citrine; RKP 41/11: Letters to and from Herbert Tracey, Records of Routledge & Kegan Paul, The Archive of British Publishing and Printing, University of Reading

[2] G. Genette, Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 1-15

[4] T. Foster, ‘The Evolution of the Book Jacket’, The Bookman, 85:505 (October 1933), p. 26

[5] T.M. Ragg to H. Tracey, 2nd April 1936, RKP 41/11

[6] W. Citrine to T.M. Ragg, 4th May 1936, RKP 28/7

[7] T.M. Ragg to W. Citrine, 5th May 1936, RKP 28/7