What do the following people all have in common? The filmmaker Ken Loach, Kenyan nationalist Tom Mboya, Blue Peter presenter Valerie Singleton, Waruhiu Itote (‘General China’, a key leader of the Mau Mau rebellion), the singer Vera Lynn, Patrick Shaw (Kenya’s most notorious police officer), Desmond Tutu, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, Jomo Kenyatta, Senator Robert Kennedy, Indira Ghandi, Mwai Kibaki, Muhammad Ali, Daniel arap Moi, Princess Anne, Pele and . . . err, naturally, Cliff Richard.

The answer is that, in one way or another, they were all supporters of the Starehe Boys School in Nairobi. Actually, I’m being a little disingenuous. Ken Loach should not really be in this list as he disliked the school so much he made a film about it. But all the others took it upon themselves to visit the school and, more often than not, help raise substantial funds to support its work.

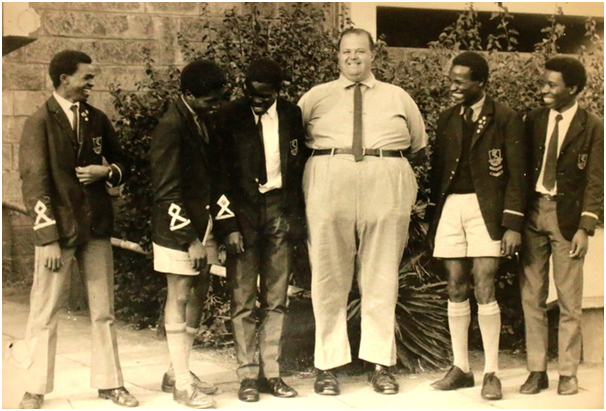

Starehe was founded in 1959 by Geoffrey Griffin, a former Intelligence Officer of the British Army who refused to renew his commission after witnessing the atrocities and the deceptions committed by both sides in the Mau Mau emergency. Wanting to give something back to his native Kenya, he set up the school to provide a home (‘starehe’ refers to a place of rest or comfort in Swahili) for impoverished boys, many of whom had become homeless orphans due to the fighting and the internment of huge numbers of the Kikuyu (see Caroline Elkin’s Britain’s Gulag). The school has gone on to become one of Kenya’s most famous and has a special place in the nation’s post-colonial history. Although it accepts a small proportion of fee-paying boarders (with fees set according to parental income), the vast majority still come from poor backgrounds and the school has clearly given these boys a chance in life that they would otherwise never have had.

On its own terms, the school has been an undoubted success. It has consistently done well in exam performance, topping the national league tables at times, and its famous marching band has provided the ‘anthem of bugles’ at many a state occasion. Yet it is the projections that have been placed upon it by a whole host of characters and institutions that make it a fascinating case study of the role of western philanthropy in the processes of decolonisation and development.

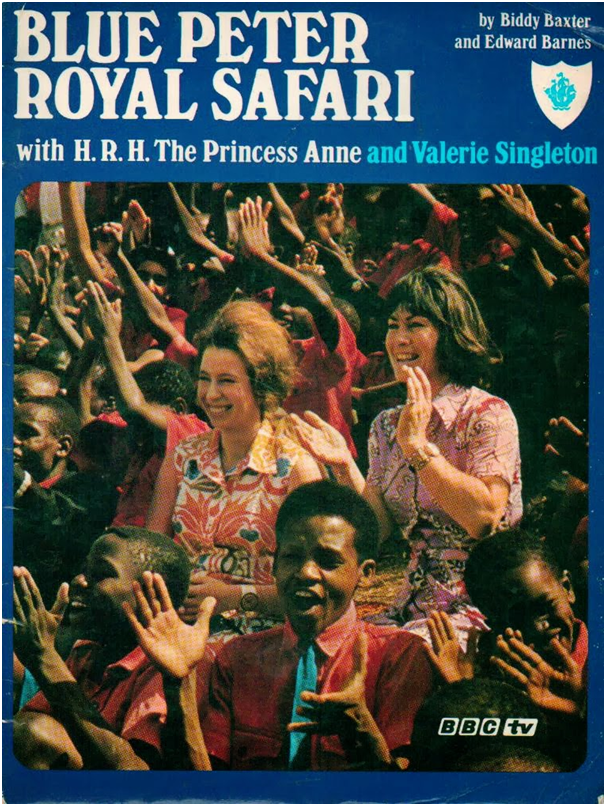

There is no doubting that the school has been a beacon of hope for liberal westerners keen to do good in Africa. From the UK, as well as the sports personalities and celebrities listed above, money has been forthcoming from the Dulverton Trust, Christian Aid, the Nuffield Foundation, Oxfam (there is a school ‘house’ named after its former director, H. Leslie Kirkley) and especially Save the Children. It was even the featured ‘Christmas appeal’ for Blue Peter in 1971, hence the Valerie Singleton connection, accompanied by Princess Anne. But this is not just a story about Britain’s post-imperial legacies. Money has also been forthcoming from the Dutch Bernard van Leer Foundation, the US Ford Foundation, the Danish Scouts (they paid for the school swimming pool), the West German Protestant Central Agency for Development as well as the governments of Denmark, Austria, Sweden, the Netherlands and the European Commission itself. The total sums given to the school are quite staggering. And still it goes on. You can give too if you’re that way inclined. There is now a UK charity devoted to raising further funds and increasing the endowment to ensure the fees of new generations of boys (and girls since 2005) can be paid well into the future.

But this is also not just a story about western aid, well spent or not. Starehe has captured the imagination of Kenya’s elites, many of whom have sent their sons as fee-paying students. Land grants from the government, donations from wealthy individuals, and contributions from business (Shell/BP in Kenya was an original backer) have all played their part. Jomo Kenyatta gave the school its motto, “Natulenge Juu” (‘Let us aim high’), while Mbiyu Koinange, a government minister and son of the prominent Kikuyu chief, Koinange Wa Mbiyu, even presented the boys with a live bull as a Christmas present.

Starehe is an anachronism. It is an English public school sweltering in the African sun. It is a leading academic institution which offers a free education to the poor and disadvantaged. And in its focus on discipline, service and character it has provided a familiar setting that affluent westerners can understand but which also has appealed to generations of nation builders since independence in 1963. Why else would a once illiterate and uneducated leading Mau Mau resistance fighter support its work (Itote actually served with the British army during the Second World War, was taught to read by Kenyatta in prison and would work alongside Griffin on Kenya’s National Youth Service)? And why else would Patrick Shaw, by all accounts a sadistically ruthless if efficient police officer who was known to deal with Nairobi’s criminal gangs at the scene of the crime, serve as the administrator for the school for quarter of a century, first as a volunteer and then as salaried member of staff paid directly by the UK Save the Children Fund?

I am withholding judgment on all of this. It is an intriguing case study and I intend to write about it soon at greater length. The history of decolonisation and development is a messy, untidy and complicated story that involves so many actors. Likewise, the role of charity, especially UK ones, do not readily lend themselves to either critique or praise. They have done so much good but many of their ventures – adventures even – have not brought the expected results.

But what is obvious is that Starehe has been one of the apparent glimmers of hope that has constantly and continually marked the history of Africa. Whether it be a late colonial official, a charity, a nationalist leader or a western pop star (Cliff Richard wasted a Geldoffian career-defining moment when he visited in 1963), all have searched for the solution for a people through the miraculous example of an isolated success story. Starehe has meant so much to so many because it has been a beacon, an example to be followed that will lead the nation and even the continent to a prosperous future.

But what is seen is what is looked for. The absence of Starehe’s replication (even girls had to wait almost half a century) is not considered. It has certainly been a success on its own terms but it has also not been the solution to development as a whole. Yet so many will continue to hope that it is so. Just as Andrew Jones wrote in his recent blog about Band Aid 30, the west will continue to search for Starehes, to provide ‘comfort’ for itself as much as the students, and it will continue to donate millions of pounds to schemes that say as much about the donor as they do the recipient.